On my first day, after checking out the building (a former hospital pavilion, hosting around 300 refugees at the time) my first task came along immediately: a (volunteer) doctor had identified a man from Syria who had suspicious insect bites and felt a specialist’s opinion was needed. I took the man and his friend to a dermatologist in the hospital located at the same premises, trying to ensure that they (for once we were there it became clear that the friend also needed help) get seen without bureaucratic hurdles or fees involved, and ideally without waiting time (to get us back to the shelter as soon as possible – so that I could use my volunteering time efficiently). The Syrian men spoke hardly any English but we did manage to patch up an anamnesis.

We were back at the shelter in less than an hour, and now part B of the task began: one of the two men had been diagnosed with scabies, a contagious disease that particularly spreads under crowded conditions where close body contact is frequent. In other words, not something you need at a refugee shelter. I therefore had to ensure that the man took a shower, discarded his clothes, and got new ones. Easier said than done when the patient doesn’t speak English or any other language I’m at least remotely familiar with; he had also just received his ‘new’ (donated) clothes a few hours before. After finding yet another set of clothes, soap, a towel and a plastic bag for the clothes to be discarded – all located in different parts of a building I was just learning to navigate - I finally managed to identify a young Afghan who was able to translate. I guided my Syrian friends to the shower and never saw them again thereafter.

My second task had become obvious: I needed to help find interpreters who, unsurprisingly, are absolutely key in handling anything to do with refugees at the moment. While there had been calls for interpreters via social media and some (volunteer) interpreters I was told were on their way I felt there was a better and rather obvious solution: get refugees to help. While some were exhausted from endless days on the road (and most didn’t speak much English), many seemed restless and quite happy to be engaged, and thus empowered. The young Afghan who had helped me talk to the Syrian patient seemed very pleased and even proud when I asked him to be involved. Giving him a sticker that identified him as a volunteer, other staff and volunteers quickly started assuming he was ‘one of us’. His English was brilliant, and from one minute to the next he was in high demand, translating during doctor’s appointments, making group announcements and helping me answer the big question that most refugees had on their minds: how can we get to Germany?

Suddenly there was news of the ‘imminent’ arrival of several hundreds of refugees at an adjacent building, which urgently needed to be converted into an additional refugee shelter. Time was ticking, and I assembled a team of volunteers to help populate the building with dorms, a kitchen and dining room, clothes and hygiene product storages (doubling as dispensaries) and a child-friendly playing area. Again, I found it obvious to ask for help also among refugees, and quite a few seemed happy to follow me.

However, as we were about to enter the building six police officers showed up. They had been called to deal with ‘aggressive refugees’. However, there hadn’t been any incidents and nobody had witnessed any aggressive behaviour. Therefore we assumed that neighbours had felt threatened by the mere sight of refugees in an otherwise empty street… this was less obvious for the team of young men I had just assembled, they did not understand what was going on and, quite understandably, were reluctant to go anywhere near the police out of fear that this would be the end of their journey to Germany, or worse, the end of their goal of being granted asylum in Europe.

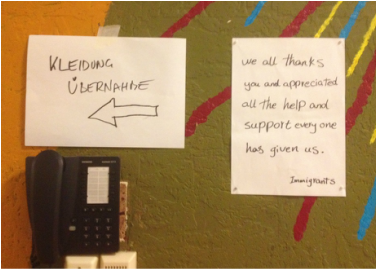

Once the police were gone we set out to set up the building as best we could, given available time (uncertain), staff (refugees and non-refugee volunteers) and items (provided by civilians and the military). It was great engaging refugees and feeling that they felt appreciated, and perhaps driven by a wish to ‘give back’. When we were almost finished, khaki-coloured buses started rolling in. However, they did not bring the hundreds of refugees we had been expecting. Instead they came to collect those that had spent the night at the other pavilion, dreaming of Germany. That night only about 50 refugees remained at the complex.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed